6. Spotting hidden opportunities

“Most people see what is, and never see what can be.”

– Albert Einstein

Why it matters

In order to innovate, we have to allow ourselves to venture into uncertain areas, because this is the area where the biggest discoveries yet to be made exist.

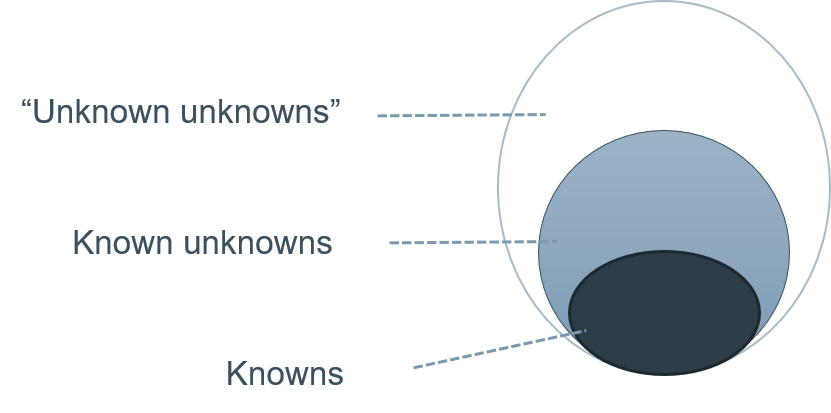

Let’s start with this simple assumption: We don’t know everything. This means that no matter how unlikely, and even how impossible it may seem, we can have confidence that there are hidden opportunities out there still to be found.

If we accept for a moment the existence of unknown unknowns, as famously defined by Donald Rumsfeld:

“But there are also unknown unknowns — there are things we do not know we don’t know.”

Then, it is easy to see that this field represents hidden opportunities. The catch-22 is: how do we spot them?

How it works

Practice 1: Push into the uncertain terrain

The first answer is logical, avoid focusing your research into the known territory. Divert your attention to the unknown territory.

As simple as the logic is, the practice is hard. This means shifting from certainty to uncertainty. This means having the courage to challenge the status quo, being OK with being called “wrong” by your surroundings many times, accepting living with doubt and never really knowing if it is going to work out. The reward and potential upside are new discoveries along the way, the gratification of trailblazing in an area few have trodden on, and who knows, if you persevere, maybe even a big payoff.

Practice 2: Exploit your curiosity

Einstein once said that he explored the boundaries of physics by imagining that he travelled on a ray of light. What would he see if he did that? Put your critical mind on the backburner for a moment, invoke your imagination to explore new areas. Try “what-if” scenarios. Don’t give up on the first try, allow yourself to play with the idea.

Practice 3: Conceive your ideas before you test them. Don’t try to do both at once!

Killing ideas is an easier task than inventing one. If you try to do them both at the same time, you will disrupt the creative process. If there is one thing you can be sure of, you are going to be wrong many times before you get it right. There is a time and space to test your hypotheses – but sequence the two phases and allow yourself to stay in the creative flow first. Then switch on your analytical side and start the hard work of testing your hypotheses.

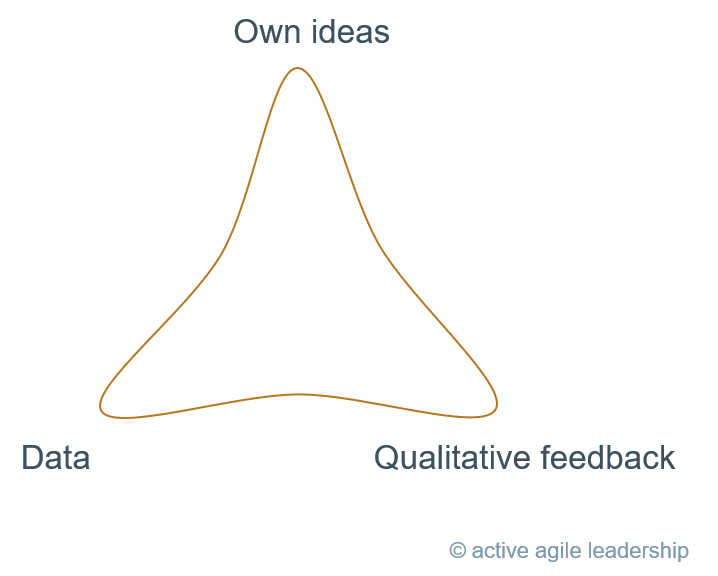

Practice 4: Triangulate your decisions

In product development, insights can come from different information sources. If the balance is off towards one source of information, we diminish our opportunities to find value over time.

Let’s for the moment assume that we are trying to figure out what product idea to build next, and there are three key information sources to turn to:

- Data – using data driven insights

- Qualitative feedback – often from focus groups

- Own ideas – injecting your own ideas to the mix

Each source carries information value but also bias. Data carries bias from the process that collected it and from time. Qualitative feedback carries bias related to the test group that gave the feedback. Our own ideas carry confirmation bias.

If we rely solely on “data driven insights” we will gravitate towards the known space (what is likely, based on data).

If we rely solely on “qualitative feedback” we will make our focus group happy, but miss pleasing the bigger crowd (that was not there).

If we rely solely on “own ideas” we bet big (sometimes your product or company) that the assumptions of a few individuals are correct.

By applying triangulation, we pay attention to our decision basis over time, avoiding unbalance caused by drifting towards one single information source alone. We grant ourselves freedom to exploit the strength of each, with the expectation that ambiguity will exist (and has information value), and the confidence that the final decision power is in our own hands.

Practice 5: Ask not what to add, but what to take away (”Less is more” )

This very simple technique seeks opportunities by exploiting something our brains rarely explores – unless explicitly nudged. The most common scenario when we get asked to get creative is that we try to add things (new features, new products). What we rarely do is explore what to take away. “What is the simplest way to solve this?” can be a very powerful question to unlock opportunities we never considered.

Creativity is for everyone

Creativity is a human trait, it’s not a role. Everyone can do it. Through practice, you can develop your ability to innovate.

There are many more techniques you can use to improve your ability to spot hidden opportunities. Consider the ones mentioned here as a good starting point.

(In the “Decision making under uncertainty” training module, we explore more of them.)

References

“Unknown unknowns”, Wikipedia

“Counterfactual thinking”, Wikipedia

“People systematically overlook subtractive changes”, Adams, G.S., Converse, B.A., Hales, A.H. et al.. Nature 592, 258–261 (2021)

“How to build your creative confidence”, David Kelley, TED2012