3. The power of small samples

Why it matters

When making decisions, the point is to reduce uncertainty, not necessarily to eliminate it.

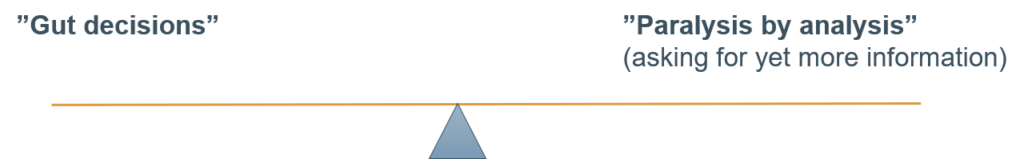

There are two scenarios we want to avoid, when it comes to making decisions under uncertainty

Why? Because there are flawed assumptions underpinning each.

Gut decisions, build on the assumption that our experience is a good predictor of the future. Overconfidence, is often a sure indicator you are too far down this side.

On the other hand, Paralysis by analysis, assumes there is a risk free option.

We want to do better than this.

How it works

When confronted with making a decision, your most crucial decision is how to make that decision. Let’s consider a few options:

- Gut decisions

- Expert opinion

- A quantitative approach

Put simply, we have two decision making systems active in our brain. Let’s call them System 1 and System 2. System 1 is what we normally refer to when we say “gut decisions”. System 2 is our analytical side. System 1 is fast and we use that when immediate action is required. So if a tiger jumps out from the trees, it’s System 1 that reacts. A drawback of System 1 is that it is generally only useful in making binary choices: yes or no, take it or leave it, stay or go. System 1 is totally useless when it comes to analyzing probabilities or when the decision involves quantifying things. It’s also prone to bias.

Expert opinions are another alternative. Experts could use System 1 or System 2, or a combination of both. But bias traps lurk here as well, with overconfidence being one. Studies have shown that most managers are statistically “overconfident” when assessing their own uncertainty, especially educated professionals.

Let’s look at a real example where expert advice fell short. In 2005, the founders of the fintech company Klarna pitch their business idea to an investor shark tank. The judging panel, made up of prominent financiers, wasn’t convinced and so their business idea came last in the competition. Today, Klarna is valued at $10.65 billion. So when considering expert advice, you have to be careful before assuming that experience from the past is a good predictor for the future.

The third approach, the quantitative approach is often easily brushed away with the misconception that it is time consuming, or requires large quantities of data. Not so.

A quantitative approach, the power of small samples

Practice: Rule of five

There is a 93.75% chance that the median of any population is between the smallest and the largest values in a random sample of five.

Imagine that you are travelling around the world, and you are asked to assess the median height of the population in the country you have just visited. The rule of five simply says that if you randomly picked a sample of five people, there’s a 93.75% chance that the median height will be among this sample of five. While this might not seem like a big deal, this means that you can be quite certain (93.75% confident) that any statement boasting that it’s outside that range is likely wrong. The real challenge in this example above is random selection, but I’m sure you get the key point of the Rule of five.

A story of applying the power of small samples

“Some years ago, I was working with a software-as-a-service provider. They got a call from a key client complaining that they urgently needed to fix a major bug. Normally, this would have meant scrambling all hands on deck to fix that bug. A very costly intervention that would mean shelving up to a week’s worth of development work in a situation where the team was already spread thin.

Armed with the understanding of the power of small samples, we tried a different approach. We randomly sampled 20 of the latest reported bugs from the last month and checked if this was indeed recurring. This took no more than an hour. It turns out that the bug called in by the key client was not. (Note that this didn’t mean that it wasn’t a valid problem for someone. It just meant that the bug was far from being the major problem). Using this data, we could concur that our priorities were indeed right. We could keep our focus and finish what we were working on, armed with the data, we could also have a more enlightened conversation with the key client.”

– Mattias Skarin

References

How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business, Douglas W. Hubbard, Wiley 2014

Effects of amount of information on judgment accuracy and confidence, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Tsai C., Klayman J., Hastie R. Vol. 107, No. 2, 2008, pp. 97-105

Using Applied Information Economics to Improve Decision Models, Douglas W. Hubbard, Lean Kanban Conference, Chicago, 2013